Roads as Catwalks

By

Even before the decline of the horse-drawn transportation industry (and the subsequent loss of jobs that nobody cares about anymore), road vehicles have been status symbols. Stage coaches were meant to show off the wealth of the occupants, while at the same time, giving them “privacy” from all the dirty riff-raff outside. People wanted a good-looking vehicle to express who they are; like they’re putting on a garment or a mask.

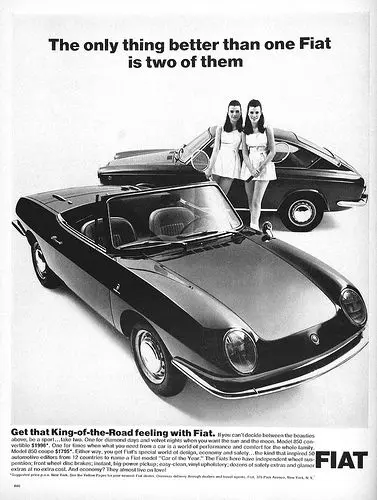

We see this pursuit of pretty cars in many vintage car ads, including headlines like Wear a Mustang to match your lipstick; or The second best shape in Italy.

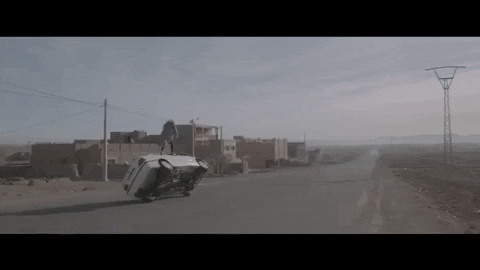

We could treat cars as massive, complicated machines that propel people to unnatural, dangerous speeds, inevitably suffering a few bumps and bruises as they navigate their chaotic environments, but instead, the road liability laws still try to keep alive the idea of cars being someone’s pretty investment; their pride and joy. If you get bumped on the crowded subway or your shoes get scuffed, well what did you expect? If you take a car onto a road though; and someone inadvertently leaves a dent, then somehow this is a big deal and whoever happened to be responsible (not you!) is forced to pay however much it costs to “fix” it. Cars are treated less like this:

Sure, car ads are no longer mysoginistic (the footage of Sophie Monk was overdone for a comedy movie), but is that it? Job done? My perspective is that the sexism was only ever a surface-level symptom of a deeper problem.

In this article, we’ll see how the laws and practices for roads and for road users have undesirable consequences; and how they reflect a superficial worldview based on oppression; entitlement; and naïveté − a view that’s not isolated to cars.

On the points of oppression and entitlement, let’s continue consideration of paying for damage after a collision. The road is a dangerous place and thousands of people die on Australian roads every year. It doesn’t make sense to bring a delicate artwork onto the dirty and dangerous road, if you’re worried about it getting damaged. If someone brings a gold-plated Rolls Royce onto the road though; and drives like they own the road, then whoever inevitably bumps into them runs the risk of going into bankruptcy to fund the repairs. Just replacing the Spirit of Ecstasy figure costs $3,000 on eBay. Sure it cost the owner the most money to bring this car onto the road, but they’ve raised the cost of living for everyone else too.

Driving an expensive car can therefore act as somewhat of a visual protection, warning people to stay away on a risk/reward basis.

This special treatment isn’t only attempted through markers of wealth though − sometimes people will stage a coup on the asphalt, deploying their own road signage:

Thankfully the NSW Road Transport Act bans people from installing their own traffic control devices; and in the US, people have similarly been punished for putting these distracting hazards on the road: Colorado father of 4 ticketed after putting a Kid Alert slow down sign in the middle of his street.

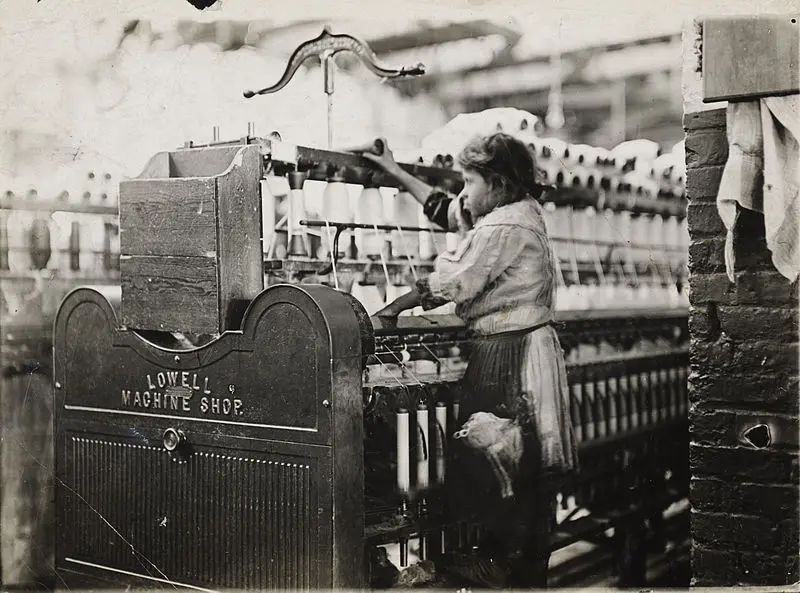

I’ve discussed previously how we already have a natural ability to notice other humans; and that this is overpowered by high-visibility colouring, especially when it deforms the silhouette. Drivers will involuntarily notice the high-visibility trap before they notice real human beings who are worth avoiding. What if someone had panicked about the “child” on the street; and swerved away, hitting a real child who had been validly standing on the footpath? What if they had crashed through a building and hit a child in their bedroom? I guess this wouldn’t be possible if the child was out at work.

In conversing with the journalist, the traffic vigilante in Colorado (🇺🇸) gave the excuse, “I agree they shouldn’t be playing in the middle of the street, but they should have the ability to ride their bikes down to the park and feel safe."

If they were following the road rules, why shouldn’t they feel safe? If the issue is that drivers aren’t looking out for cyclists, then why not have a cyclist sign, instead of a children sign? As we saw in Children Who Almost Exist, there’s a tendency to only acknowledge suffering when it’s happening to children.

While these signs are thankfully being prosecuted once in a while, I’ve yet to see anyone being prosecuted for the comparable “Baby on board” signs. Here I even stumbled across a sign with endorsement from New York’s Metropolitan Transportation Authority!

You should drive extra carefully around me, because I’m special!

Almost every time I see such a sign, there is not a baby in the car anyway, unless perhaps it’s been stuffed in the boot? Often the car will be empty and stopped, yet the sign is just as visible as ever, forcefully grabbing the attention of road users; telling them to slow down and treat this car like it’s more special than all the other vehicles. The sign is a coercive lie motivated by entitlement; and should be treated as such.

In creating unofficial signage about how special your children are, there’s obviously an assumption that other drivers will care more about children; and will treat them with more patience or sympathy − be careful in making this assumption though, in some other countries:

Warning: Viewers will likely find this video to be distressing

The video included here is an incident in 2011 in China, where a girl wanders in front of a van, starting a series of events where she’s repeatedly run over.

Another video from around that time features a scenario where a van actually reverses back over their child victim, purportedly to make sure that the child is dead. Paying for the child’s medical costs forever would be expensive.

The reactions I saw at the time to these horrific incidents were along the lines of “China is evil and isn’t it great that this doesn’t happen in the West.” I find this explanation to be unsatisfying though; and it’s reminiscent of the quote in Children Who Almost Exist where Tim Marsh was talking about writing off paedophiles as “monsters” − these aren’t hugely deviant non-humans. Sure they’ve done awful deeds, but they’re still quite similar to us, to the extent that you’d be hard-pressed picking them out. Ordinary Men by Chrisopher Browning explores how “ordinary men” ended up becoming murderers under the Nazi regime, even though everyone likes to think that if they were in Germany at the time, they’d be risking their own lives and their family’s lives, to hide Jews in the attic. Jews who were strangers to them.

There are incentive structures and laws that are guiding our behaviour. We absorb these ideas and internalise them, so that even if we claim that it’s our moral compass or our religious beliefs telling us not to reverse back over the child, I think it’s undeniable that it’s still partly due to the incentive structures put in place by government.

So why don’t these horrific scenes play out in NSW? What are the legalities of running over children here?

It might come as a surprise that in the NSW Motor Accidents Compensation Act 1999, there are differences when considering the liability of an injured adult vs an injured child − if a driver collides with a child, then even if it’s not the driver’s fault, so long as they have insurance for this accident, then they have to invoke that insurance. Going further, the child might even be at fault for the collision, but the driver and their insurer only get out of this cost if the child’s actions constitute a “serious offence” (the type that would be punishable by at least “imprisonment for 6 months”). It would be curious to know if this clause has ever been invoked, but let’s contrast this NSW law with what has played out in China.

My opinion is that the only thing stopping the video scenes from happening in NSW is the clause “if the motor vehicle … has motor accident insurance cover for the accident." Drivers therefore aren’t at risk of forking over their personal savings, like the onerous financial risk faced by the drivers in China. The government instead grabs money from the insurance company, because well, it can.

The government is assuming that the driver will have no qualms with telling their insurer that they have to pay up, but already there have been insurers asking their customers to install GPS trackers and accelerometers, for the benefit of “safe driving tips” or for gamification. The Chinese drivers are avoiding a lifetime of debt, but what is the minimum price to push someone into reversing back over the child? What if this person loses some sort of “no-claim bonus”? What if they miss out on their “safe driving badge” from their insurer’s GPS-tracking app?

2 weeks successfully swerving around child criminals

People already allow insurers to track them − is it so difficult to imagine an insurer participating in the driving of the car? What about unoccupied autonomous cars being insured by their manufacturer? If their goal is to maximise profits (as they’re legally required to do), then what’s going to happen?

Oh the autonomous car reversed back over the child? What a weird bug, we’ll have to get that fixed. What a shame.

Naïveté in Road Laws

The unintended consequences of the child insurance serves as an introductory example of the naïveté that exists in the road laws of NSW, but the main issue is that the laws have failed to keep up with technology.

In section 54 for instance, it’s deemed illegal to apply for a licence while suspended; and it’s illegal to omit the mention of your disqualification, in an application. Can’t the government check its own database to see if it should give you a licence? Why are they asking you for information that they already know?

Moving beyond the sophisticated technology of databases, the laws are lacklustre when it comes to autonomous vehicles − in fact, the law even refers to them as “automated vehicles” − a car is automated if it can open its boot; or if it can activate its interior light when someone opens a door. To lump this sort of thing into the same bucket as self-guided robots shows the laissez-faire disinterest that NSW parliament has for the future.

An automated car with a child who might be committing an act of burglary? Does this earn 6 months' imprisonment?

As cars become more autonomous, they need to learn with camera footage; and people are already installing such cameras en masse, yet there is no effort made to collect this useful data and put it to work in training robots. Imagine if the footage went into creating shared data sets and pre-trained neural networks that could then be used by private companies wanting to enter into the autonomous-vehicle space? Such facilitation would help prevent monopolies from forming around exclusive data access.

From the existing camera footage, we could even be spotting other people’s collisions in real-time and could automatically make the footage available to them, seeming as we just saw their licence plate.

We could be spotting animals and feeding this data to nation-wide models of animal population, including their death tolls. All of this valuable information being completely wasted.

GPS data is also being wasted − moving vehicles will now regularly have access to maps and live traffic information, so we always know what’s around the corner, yet speed limits have remained the same, as though we need to slowly drive into a mystery.

Once the neural networks become sufficiently sophisticated (some would argue that we’ve already reached this point), then there’s no reason the government can’t offer simulators to drivers, to improve their skills in dangerous situations. Look at the safety improvements that have happened in the aircraft industry thanks to simulation. The increase in driving after the 9/11 attacks resulted in more road deaths than the death toll from the terrorist attack itself. Driving really is that much more dangerous than flying.

Beyond the simulations for drivers, such programmatic insight into driving could even allow computers to analyse camera footage and consistently decide who was responsible for a crash − at the moment this responsibility is offloaded to private cartels.

As I’ve covered previously in Basilisk-Centered Design, there is a virtuous cycle if we give early AIs access to our current processes, so that they can keep improving. With the naïveté of the current government though, failing to see the immense opportunities, we’re stuck in a stalemate where humans are going to keep driving around in much the same way as ever, until fully autonomous cars magically appear.

Although we’ve covered some dark topics in this article, it’s allowed us to see an underlying pattern; and opportunities for improvement. Rather than treating cars as property that doesn’t belong to you − don’t touch; we can start creating laws and computer systems that allow fair access to the roads for all users, including poor people; animals; and young robots. We can enable the innovations and investments of individuals to have cascading benefits to the rest of society, rather than being squandered by insurance companies and elected officials. Sure the government might have good intentions, but can’t we stop them paving the road with this?