Is it Time for a Feudal Society in Australia?

By

Purchasing a property is a significant expense and buyers have worked hard over years to make it happen. Upon receiving the deed though, owners are not able to sleep safe and sound − there are rules and taxes, impeding on the peaceful life that owners had dreamed of. Then there’s the upkeep of the property too, but it will protect the house’s value, so it’s in the owner’s interest to take care of things − they don’t need councils bossing them around and telling them which trees they’re allowed to cut down.

Indigenous Australians get credit for being “custodians of the land”, and now they’re even getting a special spot in parliament − are property owners not looking after their land? Where’s their special influence in parliament?

This is the direction being taken in the US: in Nevada for instance, there has been talk about allowing companies with large land holdings to create Innovation Zones with their own county governments, able to set taxes, run schools and everything else that local governments do.

In Australia, the most talked-about issue for housing is the price: everyone wants a home, but some spent too much on avocado toast and now there’s a “housing affordability crisis”. In order to address this cost, Labor for instance proposed the Help to Buy initiative, where they would buy up to a 40% stake in a new home, with the tenant taking the other 60%. In terms of the supply and demand of housing, there’s also the potential to build more houses (Labor) or even more houses (The Greens). Sure the houses are even more expensive thanks to this extra buying power, but these people have now entered the market, so problem solved right?

“I’m a fixer. I fixed it”

Besides pricing, readers might also be familiar with how governments have been able to affect the architecture of housing:

Living in the roof in Paris, where taxes were based on the height of the base of the roof.

Houses in the Netherlands, where taxes were based on building width.

Governments are tasked with enabling functional markets and providing a harmonious existence to citizens. From this perspective, the housing market is a critically important area of concern. In this article, we’ll explore how the short-sighted focus on the housing market has actually been stealing away the future from younger generations; and how it has been recreating a feudal society where a land-owning class amasses wealth and power as everyone else is left to suffer.

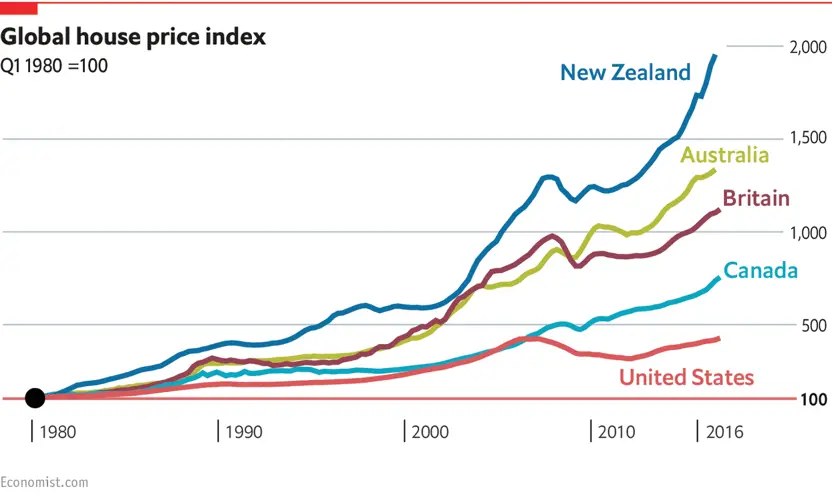

Governments have, for years, endorsed the notion that prices must go up. And up they went:

“Astronomic” house price increases in New Zealand: stuff.co.nz

A sad reality of the crisis is that few people seem to desire its end: looking at these astronomical charts, a common sentiment seems to be, “if only I’d got in early”, not “this is insane that a place to live has been turned into just another financial asset class, for speculation. The rich get richer and the poor get poorer.” As soon as anyone gets a mortgage, it seems that they’re keen for the trend to continue, now that they’ve got on board.

It’s hard to class all property owners as cold-hearted leeches on society though: there are so many voices incentivised to endorse the current state of affairs. Anyone who owns an expensive home needs potential buyers to stay interested in buying homes. Then there’s the banking industry, encouraging you to get a high mortgage, as it means years of high payments to them. Then there are all the rennovation companies, encouraging owners that they should modify their home in various ways to increase the home’s value. It doesn’t even matter if the owners actually like any of these changes: they’re told for instance that they absolutely need a bath in their home, even if they don’t use it themselves. They’ll be selling one day to a buyer, who might not use a bath either, but who is worried about what later buyers will think.

The whole system is disconnected from reality. Why did NZ house prices double from 2015 to 2022? Was it that the population of New Zealand doubled? Did the number of houses halve? No, everybody just wants to be ahead of the market, and once the prices go up, people hate the idea of losing money by accepting a lower price when selling or renting their financial asset. As one group amasses more homes, they have a greater ability to steer the market, widening the chasm between the haves and the have-nots.

If property owners are trying to keep pace with the market, it’s also worth pointing out that they might not have an accurate idea of what the market price really is, for selling or renting homes: in the US, owners were given incorrect, inflated data by RealPage, which ended up increasing real rental prices by 14.5% as landlords scrambled to keep pace with the reported figures. The Fusion Party has written recently about how absurd it is to leave such critical insight to the whims of the property industry.

The price can only get so crazy though, or people will just buy elsewhere. This has typically been the approach favoured by governments: rather than fight the property owners, hoarding an excess of liveable space and exploiting citizens, governments can encourage new houses to be built. They encourage urban sprawl − copied and pasted housing templates spring up on former farmland, with a generic, nouveau-riche name like “Rosewood”, “Bella Estate”, or “The Lakes”.

The trees get cut down, everything gets covered with concrete, no public transport gets built, and now all of these people can live in their own home, in a community afflicted by loneliness. The days are characterised by glaring heat, beaming down on Colorbond fences and perfectly-manicured lawns. The hum of crickets is sporadically drowned out by dogs wailing for the return of their owners after the end of their work-day and a 2-hour drive along monopolised toll roads. Is this what the Australian dream was supposed to be?

Exploring the outskirts of Melbourne

Fundamentally, these suburban estates lack the same way of life as the rest of the city. The idea of walkable neighbourhoods, good schools and convenient transport just doesn’t exist there. A home is more than a roof: it is meant to be a sanctuary. It’s part of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs:

Maslow’s hierarchy of human needs: each layer must be resolved before humans are able to focus on the next layer

Cause and Effect

Our environment shapes our way of life and our behaviour. So then, instead of asserting that poor people can’t afford houses because they’re poor, perhaps we should also be asking, “is the inability to own their home making the tenants poor?”

Marie Kondo encourages people to clear away clutter in order to lead a more joyful life. Jordan Peterson encourages readers to clean their room, such that they accrue better mental wellbeing, and in turn, greater career success, in a virtuous cycle.

Studies have shown that an environment can affect the learning speed of students, and we’ve previously hypothesised about the link between unappealing urban spaces and school shootings.

In cities such as San Francisco and New York, where housing is notoriously expensive, it’s commonplace for people to live with strangers; and for couples to move in together after only a few months of dating. Are New-Yorkers just better able to judge each others' character? Has cupid put something in the water?

There is evidence showing that couples who live together before marriage are actually more likely to divorce, than are couples who marry first. When housing is too expensive for singles, then logically, people will find themselves stuck living in an unsuitable relationship longer than they wish. Domestic violence is rampant in Australia, especially in Aboriginal communities, where women are 35 times more likely to be hospitalised for domestic violence, than are women from the broader population of Australia.

Living in such a state is not just bad for a victim’s physical health; it undermines their mental health and even pushes them into criminality: in England and Wales, 6 out of 10 female prisoners are victims of domestic violence.

Some might say that we need emergency housing, but the fact is that 30% of women in Australia have experienced physical violence since age 15. It would be a struggle to have enough emergency housing; and besides, it doesn’t need to grow into an emergency: why is it so difficult and time-consuming to move homes?

Gatekeeping in the Rental Industry

Monopolists love creating moats around their business models: switching costs when consumers wish to do business with a competitor. By making it difficult for people to stop doing business with you, you’re able to extract higher prices from them.

The Australian property-rental market is a difficult industry to participate in, as a renter. Upon recently moving from New York to Melbourne, everybody refused to do business with me until I was physically in Melbourne, with an Australian phone number. Most didn’t even respond to my messages, so I had to stay in hotels for weeks.

After physically visiting each property and seeing the same thing as the pictures I’d already seen online, I was asked to submit contact details for previous landlords and even my employers, going back 5 years! A Melbourne property manager admitted that they wanted to ask my boss if I was a good employee − why would my employer tell them that? This property manager is a complete stranger; why would my employer spill the tea to this person?

The Australian system of phone-call references proliferates the idea of a land-owning class pressuring commoners to put up with poor conditions, because if they complain, then they’ll miss out on a glowing reference later. Land-owners want assurance that they aren’t going to be risking their property with some uppity renter who expects the lights to work. The US practice is to get a background check: government-endorsed reports about my criminal history; and reports from credit agencies about my financial history. No messing around with the interrogation of strangers.

Besides being terrified of defamation lawsuits, another reason that references are less important in the US seems to be because they just don’t trust strangers as much as these Australian landlords and employers − they know that this stranger has no vested interest in helping them, and in fact, they might lie in favour of the tenant/employee, in order to get them off their hands. Such was the case when “Dr Death”, Jayant Patel, was given glowing letters of endorsement by the Oregon Board of Medical Examiners, who had actually restricted his practice, months earlier.

Another shock upon moving to Melbourne was the expectation that in many places, I’m expected to bring my own fridge − who is this theoretical person travelling around with some clothes in their suitcase, who doesn’t have a place to live, but who has conveniently brought along a fridge with them, to keep their drinks cold?

We hypothesised earlier that property owners are incentivised to look after their property like it was their traditional land, but that’s only plausible if they’re going to live there themselves. If they aren’t even prepared to ensure that their rental property has a fridge, then what more proof do we need that housing in Australia is increasingly becoming less of a sanctuary and more just a physical existence?

Have you thought of living in a shipping container? Image: Häuslein Tiny House Co.

Fighting Back

If a landlord gets carried away in their greed, and fails to provide liveable housing, then what recourse is available to renters in Australia? In Victoria for instance, there’s the Victorian Civil and Administrative Tribunal (VCAT). For non-urgent repairs, Victorian residents can pay for a hearing, then if the ruling goes in their favour, they can pay their rent into a VCAT escrow account (rather than to the landlord), until the repair is complete. They are not reimbursed for the filing fee, even if they win. No punishment occurs for reneging on their deal − they’re simply required to do what they were already supposed to do, at their own pace, with the tenant having to lose money and risk their reputation, in order to make it happen. Oh and if you call them, they’ll say they’re still suffering a backlog thanks to COVID (in December 2022).

In the US, tenancy disputes are conducted through the Small Claims Court, where cases cost around $25; and where parties are required to represent themselves, rather than outsourcing the job to lawyers. If the landlord (defendant) loses, then not only do they have to pay for the filing costs; the fact that they lost is reported publicly, then it’s read by credit agencies, and their financial reputation will be severely damaged.

The decisions for VCAT are published here, but without an SSL certificate, so it’s possible for anyone between you and the VCAT server (eg your landlord’s Wi-Fi router) to change the contents of the page without you knowing. Furthermore, if you were to search for a potential landlord, then if zero results show up, does that mean that your landlord is actually an honest person? What if you just made a spelling mistake? What if VCAT’s search engine had a bug? What if your landlord has changed their name? Ideally, you’d be able to look up an ABN free of charge and see definitively, “no, this business has never lost a case, since their founding in 2008”.

Why aren’t contractual breaches actually punished? Here a landlord in Canada was convicted of criminal negligence for failing to maintain smoke detectors, but it was only after a tenant died.

If it’s merely a civil case, then even if a landlord is found to be negligent, they can be covered by the negligence clause in their insurance. Yes, landlords are able to get away with failing to keep their word, and failing to maintain a place to live, for other human beings. It’s merely a monthly expense if they fail to do their job, or if they get caught lying.

By offloading all their punishments to insurers, such landlords are inevitably driving up the insurance costs for any honest landlords.

A Stacked Deck

Let’s summarise the findings so far:

- A land-owning class consults amongst each other about the fate of potential tenants.

- If a landlord drops the ball, they’re immune from punishment. The tenant bears the burden of ensuring issues are resolved.

Oh and if you buy one property, the government helps you to buy a subsequent one, by giving you a 50% tax break on your capital gains.

How could this possibly be any more skewed towards land-owners? Sometimes I hear landlords complain, “oh the laws are too lenient for tenants to break their lease”. In some European nations though, it is not a crime to escape from prison:

Countries in Europe where escaping from prison is not a crime

Wanting to escape from prison is just human nature; it’s not viewed to be a trait of criminals; it’s not something malicious or evil.

If someone wants to escape your rental property, they’ll have a significant amount of hassle and moving expenses − it’s probably been nagging at them for a long time, that this just isn’t a place where they can feel comfortable. You had all the advantages in your favour: your customer was already right there in your store. If they’re trying to bust their way out of your store, you probably deserve to lose a customer!

Forcing tenants to stay a whole year then mess around with weeks of inspections denies the reality that sometimes tenants need to leave in a hurry. What if there’s domestic violence? What if someone is kicked out of home, for being gay?

Even if this gay person can afford a place and even if they get an appointment to visit the home, when it turns out they haven’t rented before, it’s a safe bet that their application will be put on the back-burner, in the hopes that someone else will come along, who has already kissed the ring of the land-owning class. The gay potential tenant will have their criminal history reviewed, but they don’t get to see the criminal background of the landlord, who has keys to their new home.

Here we’re assuming of course that the landlord has still kept the application on the back-burner, rather than rejecting them outright, for being gay, Muslim, pregnant or black. Of course landlords wouldn’t do that.

If tenants were able to break their leases easily, then sure, it would be less appealing to be a landlord, but so what? Should society really be incentivising people to buy someone else’s home, as a money-making endeavour? Why can’t they put their money on stocks or NFTs? Are these owners especially skilled at maintaining their properties or optimising the living arrangements of their tenants? No, they’re just rich; and the skewed property market is allowing them to get even richer. Instead of starting with the assumption that rich property tycoons need to make money on their investments, let’s start with the assumption that people in Australia need a place that grants them safety and allows them to flourish as productive participants in our society.

Public Housing

No discussion of housing policy would be complete without discussing the option of having the government take responsibility for tenants. In Sweden, 18% of people live in municipal housing cooperatives; and in Singapore, 79% live in public housing. The drawback to public housing though, or any government project, is that it is largely immune from being competitive in the market. Public housing projects can turn into crime-filled ghettos; and if a government bureaucrat was looking after a property, then why would they be any more proactive or competent than the current land-owning class?

In Australia, 4.2% of housing stock is public housing, but for some reason (💉), applicants often reject offers to live in public housing estates; or apply for transfers.

“Some of these estates have become established centres of heroin dealing and drug use."

Resolving the Crisis

Where is the logical conclusion to this saga? Are housing prices ever meant to “get back to normal”? What’s supposed to happen with the gulf where some people own zero properties, while others keep collecting more? We’ve all played Monopoly; we know what happens when someone gets the slightest advantage.

Both major parties in Australia will only endorse strategies that continue sending property prices higher, making the problem worse and worse for subsequent generations.

It is too late to ensure everyone owns a home, and it is only creating new problems when we build depression-inducing, pseudo-Australian monstrosities on the outskirts of our cities. We have existing, government-funded infrastructure in the heart of liveable cities: the most liveable cities in the world! Why not make the most of them by increasing the density there?

There are a few strategies which could help to ensure a fairer allocation of properties, and a better alignment towards the mental health of tenants:

- Stop giving property owners tax discounts for their real-estate gains. Why do they deserve it? It’s just a way for the rich to get richer. If owning one home allows you to more easily accrue wealth and purchase a subsequent home, then this is exponential growth.

- Stop the sale of properties to non-residents − if they’re not allowed to live here, they have no business controlling housing here. They’re guaranteed to be the least-involved landlords; and they’re hoping to profit from our efforts to create a harmonious society. We could do it a whole lot easier without an absentee landlord. Canada has gone even further, restricting sales just to citizens, refugees and permanent residents.

- Remove stamp duty − it increases the switching costs of housing, encouraging people to remain in suboptimal situations with wasted space or long commutes.

- Stop giving tax discounts for vacant land − companies should not be encouraged to squander our resources.

- A government-run credit bureau, giving a reliable heuristic for a tenant’s suitability, using criminal history and tax records. The government could act as a trusted third-party, merely saying “this tenant has never been evicted and their yearly income is at least 3× the rent”, rather than the current paradigm of phone calls to strangers; unverifiable screenshots; and a chance to snoop through all of the financial transactions in a tenant’s bank statement.

- A government-run database of landlords. Potential tenants can see the criminal background of their landlords. Once a lease starts, send the info again, in case the landlord managed to hide it before move-in.

- Easily accessible data showing whether or not a landlord has been successfully sued; and whether they’ve broken their leasing arrangements before, so bad landlords are pushed out of the market.

- Open-source software for running a federated property-management company. If tenants could swap apartments within the same federation, it would be less severe than breaking a lease. If property managers were following a standardised process, then some sort of revenue-sharing arrangement could also be feasible.

- Suggestions for standardised leases, akin to the MIT or GNU licenses in the software world. Why is every landlord coming up with their own lease?

- Stop building cities for cars. Cities should be built for people, animals and robots. Prioritising cars results in urban sprawl taking over.

- Introduce a form of Harberger Tax, whereby land-owners pay an ongoing tax proportional to a self-assessed valuation of their property. At any time, someone can come along and purchase the property for the self-reported price.

Some people may feel that it doesn’t affect them, that they’re sorted because they’ll be inhereting from their parents, but what is the chance that your parents rack up an expensive medical bill on the way out? What if your parents get scammed out of their savings? What if your parents' waterfront home gets washed away by the rising sea levels they helped to create? These are non-neglible risks, and the housing crisis strikes at the heart of Australian culture, as it’s a matter of fairness.

Property moguls are putting a stranglehold on our places to live and our governments have been enabling them to get away with it. It’s about time that our governments create protections for us, ensuring that we can live a life of peace and harmony, not the life of an indentured serf.